Ventilating the Acidotic Patient: VCV Strategies to Preserve Compensation

Preserve Compensation Without Breaking the Lung

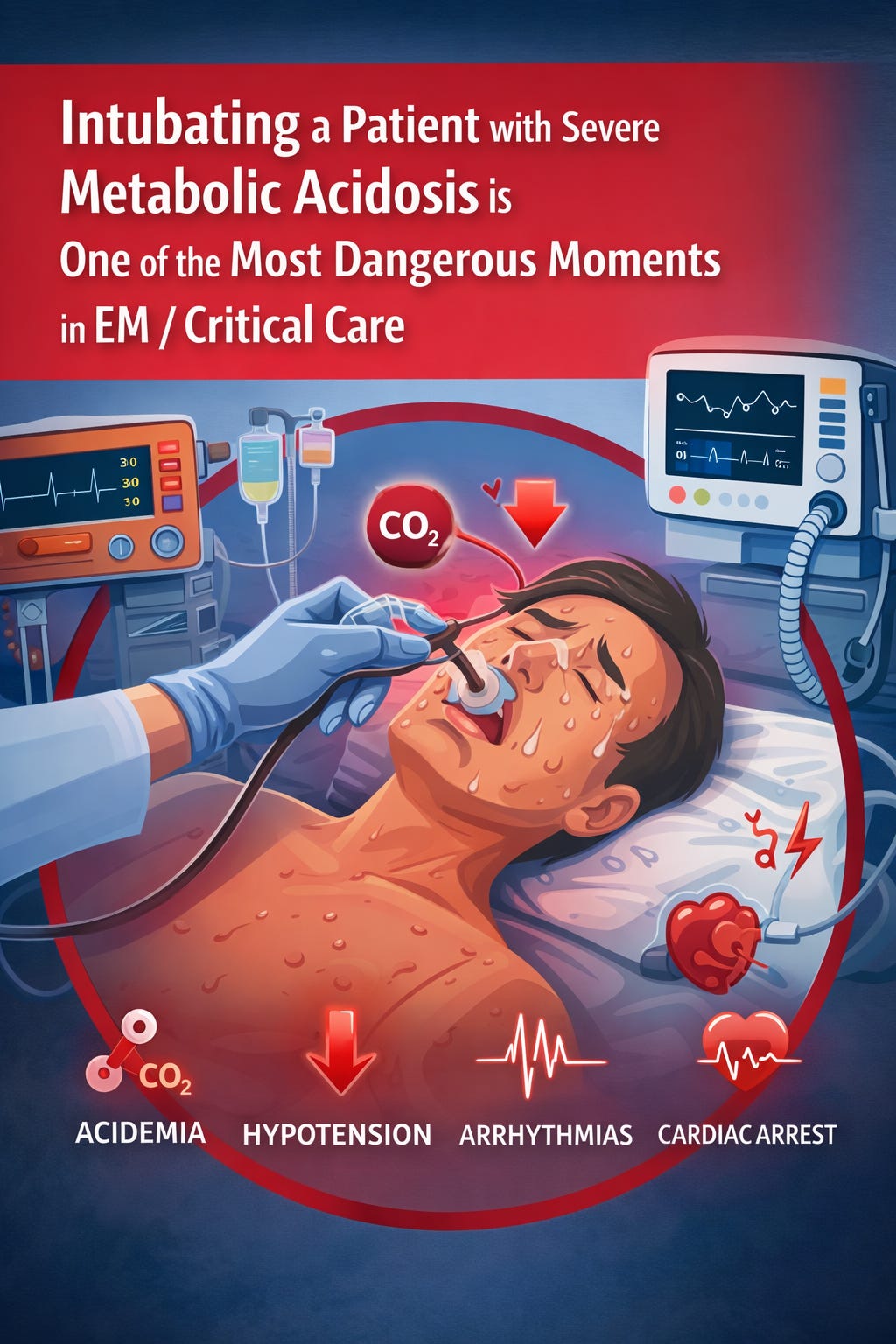

Intubating a patient with severe metabolic acidosis is one of the most dangerous moments in EM/critical care. The risk is not hypoxia alone—it is the abrupt loss of respiratory compensation, which can precipitate rapid worsening of acidemia, hypotension, malignant arrhythmias, and cardiac arrest.

Always keep a higher threshold for intubation in such patients.

Patients with diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), lactic acidosis, renal failure, or toxin-induced metabolic acidosis often present with extremely high minute ventilation, reflecting profound physiologic stress and an intact compensatory response. This pattern is especially common in the sickest patients we intubate. Yet, despite being central to survival, this compensatory hyperventilation is frequently under-recognized or unintentionally abandoned at the time of intubation. Once sedated and paralyzed, the patient’s ability to buffer acidemia disappears unless it is deliberately recreated on the ventilator (Jung et al., 2019; REBEL EM).

The core physiologic problem

In metabolic acidosis, the normal physiologic response is increased tidal volume with tachypnea, allowing PaCO₂ to fall and pH to be buffered (Jung et al., 2019).

Intubation interrupts this adaptation. If minute ventilation drops—even briefly—PaCO₂ rises rapidly, pH worsens, and cardiovascular collapse may follow (Frakes et al., 2023; Latona et al., 2025).

This principle is emphasized repeatedly in bedside physiology discussions, including the REBEL EM ventilation framework for severe metabolic acidosis, which highlights post-intubation CO₂ retention as a common and preventable cause of deterioration .

The ventilator must temporarily replace the patient’s compensatory hyperventilation.

What you are (and are not) trying to achieve

You are not trying to normalize pH.

Expert guidance recommends:

Accepting partial compensation

Targeting pH ≥ 7.15

Avoiding sudden loss of ventilation while treating the underlying cause

French SRLF/SFMU expert-panel guidelines explicitly caution against aggressive normalization and emphasize that ventilatory compensation is supportive and time-limited (Jung et al., 2019).

Why use volume-controlled ventilation (VCV)?

VCV is preferred because it provides:

Predictable minute ventilation

Reliable control of PaCO₂

Easier titration in rapidly changing physiology

Pressure-limited modes may fail to deliver sufficient ventilation when compensatory demand is extreme (Frakes et al., 2023).

Practical VCV setup in severe metabolic acidosis

Tidal Volume (VT)

6–8 mL/kg PBW if lungs are relatively normal

Stay near 6 mL/kg if ARDS or lung injury is present

Monitor plateau pressure closely

Case-level data in profound lactic acidosis suggest that, when ARDS is absent, slight deviation above strict 6 mL/kg may help maintain acid–base balance without immediate lung injury (Frakes et al., 2023), acknowledging that even short-term non-injurious ventilation can cause lung injury if prolonged (Wolthuis et al., 2009).

Respiratory Rate (RR): the primary lever

Start higher than default ventilator settings

24–35 breaths/min is commonly required

Increase incrementally while watching for:

Auto-PEEP

Rising plateau pressures

Hemodynamic compromise

Expert guidance consistently recommends raising RR before VT in metabolic acidosis (Jung et al., 2019; Tiruvoipati et al., 2020).

Minute ventilation: think explicitly

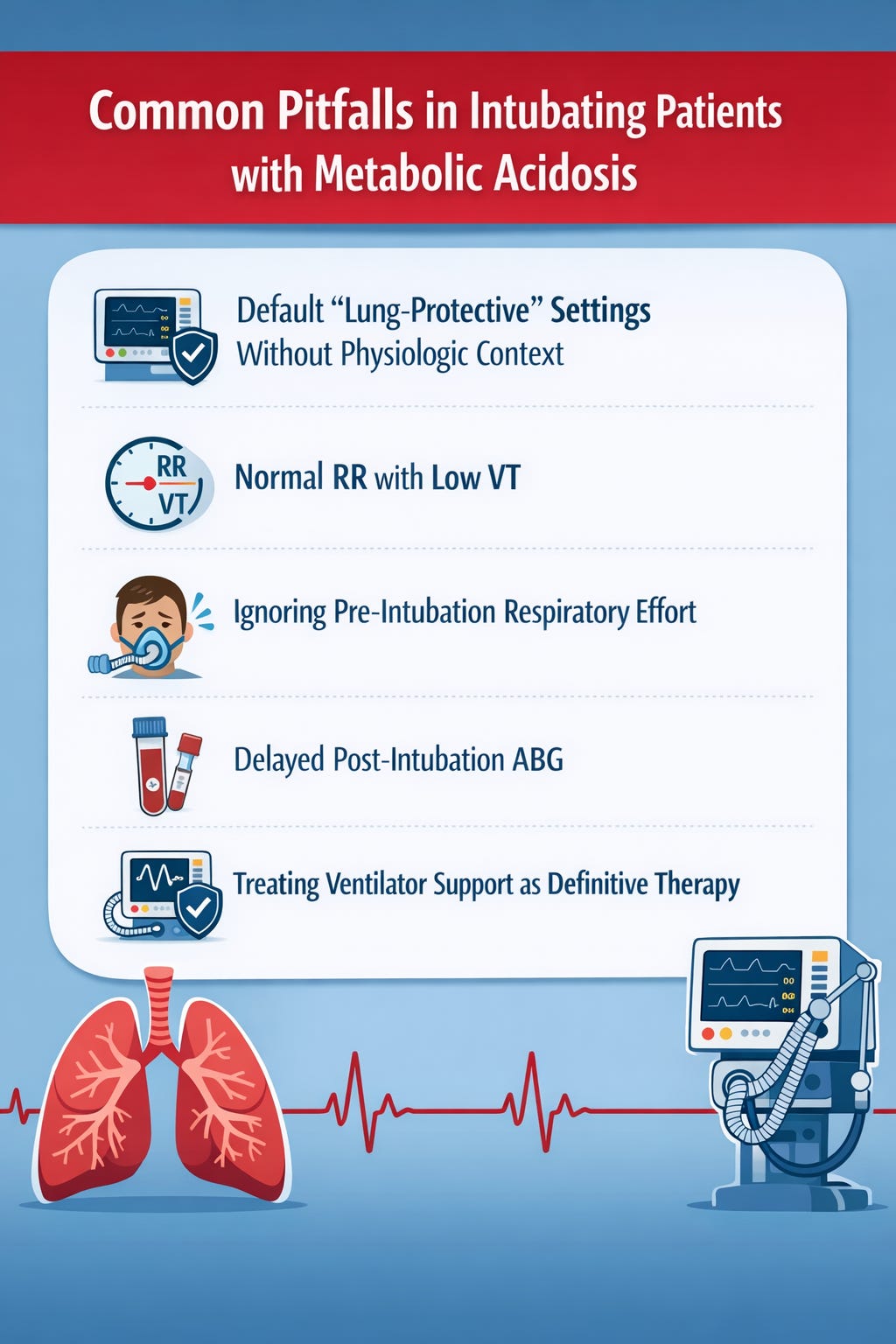

Normal ventilator defaults are almost always inadequate in severe metabolic acidosis.

A practical physiology-based approach:

Estimate expected PaCO₂ using Winter’s equation

Match minute ventilation to pre-intubation compensation

Recheck ABG within 20–30 minutes

Adjust RR (and VT if needed)

This approach mirrors the REBEL EM framework for managing post-intubation ventilation in severe metabolic acidosis (REBEL EM,2018).

PEEP

Use standard PEEP (~5 cm H₂O) unless oxygenation or ARDS physiology dictates otherwise

Excessive PEEP may worsen venous return in acidotic, vasodilated patients (Jung et al., 2019)

Monitoring (non-negotiable)

Serial ABGs

Continuous EtCO₂ trends

Plateau pressure

Hemodynamics

While EtCO₂ may underestimate PaCO₂ in shock, trending values still correlate meaningfully with arterial measurements and help guide ventilation adjustments (Praveenraj et al., 2023; Ciabattoni et al., 2025).

Special situations

Diabetic ketoacidosis

Recent case series describe ventilator-assisted preoxygenation with high minute ventilation during apnea to preserve respiratory compensation around the time of intubation (Latona et al., 2025). In patients with severe DKA, the airway is not only anatomically challenging but also physiologically difficult, with profound dependence on continuous hyperventilation to maintain pH.

For this reason, pre-ventilation—deliberately providing high minute ventilation in parallel with preoxygenation—should be considered during airway preparation. The principle remains unchanged: never allow ventilation to suddenly fall, either during induction, apnea, or immediately after intubation.

Lactic acidosis and toxin-related acidosis

Patients with severe lactic acidosis or toxin-induced metabolic acidosis often require extraordinarily high minute ventilation to maintain acid–base balance. In these physiologically fragile airways, pre-ventilation alongside preoxygenation becomes critical to prevent abrupt loss of compensatory ventilation.

Post-intubation deterioration in this population is frequently driven by CO₂ retention rather than hypoxia, particularly when minute ventilation is not rapidly re-established after sedation and paralysis (Frakes et al., 2023; REBEL EM).

Take-home framework

For intubated patients with severe metabolic acidosis and relatively normal lungs:

Use VCV

Preserve compensation with high minute ventilation (REBEL EM)

Increase RR first, adjust I:E ratio ensuring, no AUTO-PEEP ,then VT up to 8 mL/kg PBW if needed

Target pH ≥ 7.15, not normalization

Treat the underlying cause aggressively and early

If the ventilator does not replace the patient’s work of breathing, the physiology will punish you for it.

CAUTION !!

This synthesis integrates expert guidelines, case-level evidence, and bedside physiology. It is intended for educational discussion and should be applied with clinical judgment in individual patients.

References

REBEL EM.

Simplifying Mechanical Ventilation – Part 3: Severe Metabolic Acidosis.

Available at: https://rebelem.com/simplifying-mechanical-ventilation-part-3-severe-metabolic-acidosis/

(Accessed for physiologic framework on matching compensatory minute ventilation post-intubation.)Jung B, Martinez M, Claessens Y, et al.

Diagnosis and management of metabolic acidosis: guidelines from a French expert panel.

Annals of Intensive Care. 2019;9:92.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s13613-019-0563-2Frakes M, McWade J, Ender V, Cohen J, Wilcox S.

Ventilator management in metformin-associated lactic acidosis: a case report.

Air Medical Journal. 2023;42(5):300–302.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amj.2023.04.001Latona A, Pellatt R, Wedgwood D, Keijzers G, Grant S.

Ventilator-assisted preoxygenation for patients with diabetic ketoacidosis: a novel case series.

Air Medical Journal. 2025;44(3):217–222.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amj.2025.01.006Tiruvoipati R, Gupta S, Pilcher D, Bailey M.

Management of hypercapnia in critically ill mechanically ventilated patients: a narrative review.

Journal of the Intensive Care Society. 2020;21(4):327–333.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1751143720915666Wolthuis EK, Vlaar AP, Choi G, et al.

Mechanical ventilation using non-injurious ventilation settings causes lung injury in the absence of pre-existing lung injury in healthy mice.

Critical Care. 2009;13:R1.

https://doi.org/10.1186/cc7688Praveenraj M, Kalabarathi S, Minolin M.

Correlation of end-tidal CO₂ and arterial blood gas parameters in predicting metabolic acidosis in mechanically ventilated ICU patients.

Cardiometry. 2023;26:737–741.

https://doi.org/10.18137/cardiometry.2023.26.737741Ciabattoni A, Chiumello D, Mancusi S, et al.

Acid–base status in critically ill patients: physicochemical versus traditional approach.

Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025;14(9):3227.

https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14093227

This is an excellent physiology-forward write-up, and the framing is exactly right: in severe metabolic acidosis, the peri-intubation killer often isn’t oxygenation, it’s loss of compensatory minute ventilation and rapid CO₂ rise → pH cliff → hemodynamic collapse.

I especially appreciate the practical emphasis on VCV for predictable ventilation, using RR as the primary lever, and explicitly sanity-checking targets with Winter’s equation rather than default vent settings that are almost always too “gentle” for these patients.

One bedside pearl I’d add: measure what the patient is doing before you take it away. Watching pre-intubation RR/VT (or NIV-delivered minute ventilation during preoxygenation) gives you a concrete “compensation target,” then re-check an ABG early (20–30 min) and titrate while vigilantly screening for auto-PEEP/air-trapping and hemodynamic intolerance.

High yield, clinically honest, and very teachable; thank you for putting words and numbers to what many of us feel at the bedside!

Does non-invasive monitoring (Transcutaneous) of blood gas by Sentec (both tcPco2 and tcPcCo2 as PtC- can help in these patients?