Modern Approach to Shock in Acute Care: recognize early, act fast, save lives

From early perfusion markers to ultrasound-guided, personalized resuscitation

Shock is not just hypotension.

At its core, shock is a state of systemic hypoperfusion, where tissues fail to receive adequate oxygen delivery (Farkas, 2024).

The danger?

👉 Shock can exist with normal blood pressure

👉 Cardiac output may even be high (as in early sepsis) — yet organs are starving due to microvascular dysfunction

As Josh Farkas (2024) puts it:

“Shock is like obscenity. After a while, you know it when you see it.”

Left untreated, shock becomes the final common pathway to multiorgan failure and death.

But when recognized early — it is often reversible.

🚨 How to identify shock BEFORE vitals collapse

Don’t wait for MAP <65.

Early shock hides in perfusion markers and trends (Farkas, 2024).

⚠️ Hemodynamics

• Falling BP or big drop from baseline

• Shock Index (HR/SBP) >0.8 = instability

🧊 Peripheral perfusion

• Cold extremities

• Capillary refill >5 sec

• Mottling (highly specific for hypoperfusion)

🚽 Kidneys

• Urine output <0.5 ml/kg/hr

• Dark concentrated urine

🧠 Brain

• New delirium or altered mentation

🧪 Metabolism

• Lactate >4 mmol/L (but normal doesn’t exclude shock)

• Sudden rise in anion gap = occult hypoperfusion

Perfusion failure comes before hypotension.

Only FOUR types of shock (keep it simple)

In the ED, all shock fits into:

1️⃣ Hypovolemic

2️⃣ Distributive (sepsis, anaphylaxis, endocrine, neurogenic)

3️⃣ Cardiogenic

4️⃣ Obstructive

(Pannu, 2023; Pérez et al., 2024)

⚠️ As shock progresses, it often becomes mixed shock:

• Sepsis → septic cardiomyopathy

• Cardiogenic shock → systemic inflammation & vasodilation

(Gidwani & Gómez, 2017)

⚡ The acute care mindset: SED approach to shock

👉 STABILIZE

👉 EXCLUDE IMMEDIATE DANGERS

👉 DISPOSITION & DEFINITIVE CARE

This keeps you fast, focused, and safe.

🅢 STABILIZE — treat first, don’t wait for diagnosis

🚑 Immediate priorities

• Airway & oxygen

• IV access (don’t delay pressors for central line)

• Monitoring (ECG, BP, SpO₂, urine output, lactate)

Use early shock bundles (first 30 minutes)

Early protocolized care improves outcomes (Hasanin et al., 2024; Bokade & Deshmukh, 2025):

✔ Fluids in small boluses (250–500 ml)

✔ Early vasopressors if MAP inadequate

✔ Labs + lactate

✔ Bedside ultrasound (POCUS)

✔ Treat likely cause

Avoid blind fluid flooding — many shocked patients are not fluid responsive or tolerant. (individualised approach)

💧 POCUS-guided initial fluid therapy in shock

In modern shock care, the goal is no longer to “give fluids liberally,” but to administer fluids only when they will meaningfully increase cardiac output without causing harmful congestion. Point-of-care ultrasound enables this individualized balance by simultaneously assessing fluid responsiveness (will stroke volume increase?) and fluid tolerance (can the patient safely accept more volume?).

Dynamic flow markers such as LVOT VTI or aortic velocity changes during passive leg raise or small boluses identify patients likely to augment cardiac output (Pérez et al., 2024; Noor et al., 2025; Kenny et al., 2023), while lung ultrasound and venous Doppler (IVC, portal, hepatic, intrarenal veins—VExUS) detect early pulmonary and systemic congestion, signaling when further fluids may worsen organ dysfunction (Huard et al., 2024; Argaiz et al., 2021; Martínez et al., 2025).

Importantly, a patient may be fluid responsive but not fluid tolerant—for example, showing increased stroke volume yet already developing lung B-lines or venous congestion—where giving more fluid would likely cause harm. Conversely, some patients may appear fluid tolerant but not fluid responsive, meaning additional volume will not improve flow and only delays definitive therapy.

The only scenario where continued fluid loading is appropriate is when the patient is both fluid responsive and fluid tolerant.

This “flow versus congestion” framework helps clinicians decide when to give, test, stop, or even actively remove fluid. Given that positive fluid balance is strongly linked to higher mortality, acute kidney injury, and respiratory failure (Messmer et al., 2020), and that POCUS-guided resuscitation improves lactate clearance, reduces vasopressor duration, and likely lowers mortality (Basmaji et al., 2024; Li et al., 2025), ultrasound-guided fluid therapy represents a major advance in personalized shock resuscitation.

💉 Vasopressors early when needed

Norepinephrine is a safe broad default for undifferentiated shock

(De Backer et al., 2010; Farkas, 2024)

👉 Peripheral norepinephrine is acceptable short-term with monitoring.

*(more about escalating vasopressors adn inontropes in different post)

🦠 If sepsis possible → antibiotics early

Even one broad agent early beats delay (Farkas, 2024).

🅔 EXCLUDE IMMEDIATE DANGERS — use POCUS aggressively

🔍 RUSH protocol = Pump – Tank – Pipes

🫀 Pump (heart)

• LV function

• RV dilation/strain (PE)

• Pericardial effusion/tamponade

🛢 Tank (volume)

• IVC size/collapsibility

• Lung B-lines (pulmonary edema)

• Pleural/abdominal fluid

🚰 Pipes (vessels)

• Aorta (AAA/dissection)

• Lower limb veins (DVT)

• Often with EFAST

(Perera et al., 2010; Ghane et al., 2015; Keikha et al., 2018)

📊 Accuracy

RUSH sensitivity ~87%

specificity ~98%

(Keikha et al., 2018)

Often faster than labs or CT in early shock.

➕ Extended RUSH

Modern resuscitative ultrasound adds:

• Lung water

• Venous congestion

• Serial echo reassessment

to guide fluid tolerance and perfusion (Pérez et al., 2024; Martínez et al., 2025).

RUSH VTI — quantitative resuscitation

Adding LVOT Velocity Time Integral (VTI) allows:

✔ Stroke volume measurement

✔ Fluid responsiveness testing

✔ Distinguishing high-output vs low-output shock

(Blanco et al., 2015; Martínez et al., 2025)

👉 Move from “looks good” to numbers-guided physiology.

Hemodynamic optimization: treat physiology, not BP

Instead of “more fluids, more pressors”, assess:

✔ Preload

✔ Contractility

✔ Vascular tone

✔ Heart rate/rhythm

✔ Organ perfusion

(Farkas, 2024)

Examples:

• Low output → inotrope (dobutamine, epinephrine, milrinone)

• Pure vasodilation → vasopressors

• RV failure → vasopressin + epinephrine often better

• Volume responsive → fluids

The Golden Hour of shock

Shock is time-dependent — like STEMI or stroke.

Early:

• recognition

• classification

• targeted therapy

dramatically improves outcomes (Marini et al., 2024).

Delay = metabolic collapse → multiorgan failure.

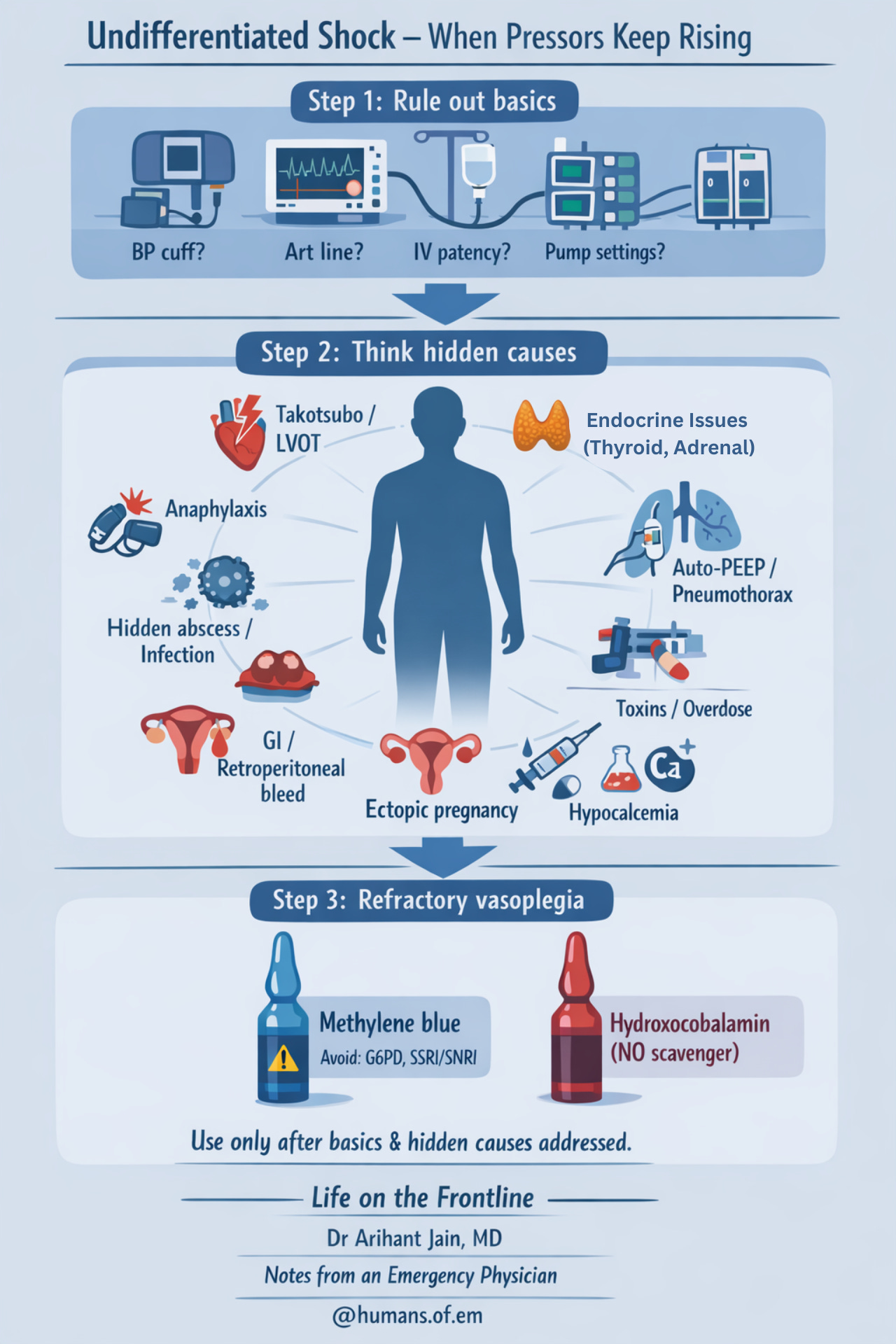

Undifferentiated shock – when pressors keep rising

When common causes are treated and patient worsens — pause and reassess.

Step 1: Rule out basics

• Check BP machine, arterial line, IV access, pumps

• Repeat full RUSH / extended RUSH

Step 2: Think hidden causes

• Anaphylaxis (can be subtle)

• Adrenal crisis

• Severe hypothyroidism

• Hidden abscess or undrained infection

• Internal bleeding

– GI bleed (melena)

– retroperitoneal bleed

– ectopic pregnancy

• Stress cardiomyopathy (Takotsubo)

• Dynamic LVOT obstruction

– SAM on echo

– late-peaking “dagger” LVOT flow

– narrow pulse pressure

– BP worsens with pressors

(Farkas, 2024)

• Toxins / overdose

• Severe acidosis

→ increase minute ventilation

→ consider isotonic bicarbonate

• Hypocalcemia

Step 3: Refractory vasoplegia

Consider adjuncts when appropriate:

• Methylene blue (NO pathway inhibition)

(Ibarra-Estrada et al., 2023; Pruna et al., 2023)

⚠ Avoid in G6PD deficiency, SSRI/SNRI use

• Hydroxocobalamin (NO scavenger)

(Patel et al., 2023)

References

Farkas JD. Shock & vasopressors. In: Internet Book of Critical Care (IBCC). EMCrit Project; 2024. Accessed 2024.

De Backer D, Cecconi M, Chew M, et al. A plea for personalization of the hemodynamic management of septic shock. Crit Care. 2022;26:372. doi:10.1186/s13054-022-04255-y

Pannu A. Circulatory shock in adults in the emergency department. Turk J Emerg Med. 2023;23:139-148. doi:10.4103/2452-2473.367400

Hasanin A, Sanfilippo F, Dünser M, et al. The MINUTES bundle for the initial 30 min management of undifferentiated circulatory shock. Int J Emerg Med. 2024;17:19. doi:10.1186/s12245-024-00660-y

Bokade R, Deshmukh S. Impact of a protocol-driven shock bundle on outcomes in patients with shock. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2025;29:S231-S234. doi:10.5005/jaypee-journals-10071-24933.175

Pérez C, Diaz-Caicedo D, Hernández D, et al. Critical care ultrasound in shock: comprehensive review of protocols. J Clin Med. 2024;13:5344. doi:10.3390/jcm13185344

McLean AS. Echocardiography in shock management. Crit Care. 2016;20:275. doi:10.1186/s13054-016-1401-7

Jentzer JC, Tabi M, Burstein B. Managing the first 120 minutes of cardiogenic shock. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2021;27:416-425. doi:10.1097/MCC.0000000000000839

Tehrani BN, Truesdell AG, Psotka MA, et al. A standardized approach to cardiogenic shock. JACC Heart Fail. 2020;8:879-891. doi:10.1016/j.jchf.2020.09.005

Mahajna A, Bolotin G, Lorusso R. Comprehensive review of cardiogenic shock management strategies. Eur Heart J Suppl. 2025;27:iv4-iv11. doi:10.1093/eurheartjsupp/suae125

Papolos A, Kenigsberg B, Berg DD, et al. Cardiogenic shock outcomes with versus without shock teams. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;78:1309-1317. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2021.07.044

Belfioretti L, Francioni M, Battistoni I, et al. Multidisciplinary team-based approach to cardiogenic shock: 10-year experience. J Clin Med. 2024;13:2101. doi:10.3390/jcm13072101

Stewart B, Maier RV. Shock, resuscitation, and fluid therapy strategies in acute care surgery. In: Intensive Care for Emergency Surgeons. Springer; 2019.

Perera P, Mailhot T, Riley D, Mandavia D. The RUSH exam: rapid ultrasound in shock. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2010;28:29-56. doi:10.1016/j.emc.2009.09.010

Keikha M, Salehi-Marzijarani M, Nejat R, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of RUSH exam: systematic review and meta-analysis. Bull Emerg Trauma. 2018;6:271-278. doi:10.29252/beat-060402

Ghane M, Gharib M, Ebrahimi A, et al. Accuracy of early RUSH exam in critically ill patients. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2015;8:5-10. doi:10.4103/0974-2700.145406

Blanco P, Aguiar F, Blaivas M. RUSH velocity–time integral protocol. J Ultrasound Med. 2015;34:805-813. doi:10.7863/ultra.15.14.08059

Martínez A, Luordo D, Rodríguez-Moreno J, et al. POCUS for monitoring and resuscitation in shock. Intern Emerg Med. 2025;20:1505-1515. doi:10.1007/s11739-025-03898-3

Noor A, Liu M, Jarman A, et al. Point-of-care ultrasound in hemodynamic assessment. Biomedicines. 2025;13:1426. doi:10.3390/biomedicines13061426

Huard K, Joyal R, Beaubien-Souligny W. POCUS assessment of fluid responsiveness and tolerance. J Transl Crit Care Med. 2024. doi:10.1097/JTCCM-D-24-00012

Argaiz E, Koratala A, Reisinger N. Comprehensive fluid status assessment with ultrasound. Kidney360. 2021;2:1326-1338. doi:10.34067/KID.0006482020

Kenny JS, Prager R, Rola P, et al. Unifying fluid responsiveness and tolerance with physiology. Crit Care Explor. 2023;5:e1022. doi:10.1097/CCE.0000000000001022

Messmer AS, Zingg C, Müller M, et al. Fluid overload and mortality in critical care. Crit Care Med. 2020;48:186-193. doi:10.1097/CCM.0000000000004617

Basmaji J, Arntfield R, Desai K, et al. POCUS-guided resuscitation in shock: systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 2024;52:1661-1673. doi:10.1097/CCM.0000000000006399

Li Q, Xu J, Zhao J, et al. Ultrasound-guided fluid management in septic shock: RCT. J Trauma Nurs. 2025;32:90-99. doi:10.1097/JTN.0000000000000839

Romero-González G, Koratala A, Kazory A, Ronco C. POCUS for congestion and diuretic strategies. Intensive Care Med. 2025;51:646-647. doi:10.1007/s00134-025-07801-8

Gidwani UK, Gómez H. Mixed shock: evolving concepts. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2017;23:416-423.

Ibarra-Estrada M, et al. Methylene blue in refractory septic shock. Crit Care. 2023.

Patel JJ, et al. Hydroxocobalamin in refractory vasoplegic shock. Chest. 2023.

This is an excellent, clinically grounded synthesis because it keeps the center of gravity where it belongs: shock is a perfusion problem first, a blood pressure problem second.

I especially like the way you implicitly push readers toward a physiology-forward loop at the bedside: identify the dominant phenotype (distributive vs hypovolemic vs cardiogenic vs obstructive), confirm it with rapid markers (mental status, skin temp/mottling, cap refill, urine output, lactate trend), and then use dynamic assessment to decide whether the next intervention should be fluid, vasopressor/inotrope, or immediate source control. That mindset prevents two common failure modes in acute care: (1) reflexive “more fluids” in vasoplegia with capillary leak/right-heart strain, and (2) chasing a MAP number while tissue perfusion continues to deteriorate.

Your emphasis on early norepinephrine when indicated, timely antibiotics/source control in suspected sepsis, and point-of-care ultrasound as a discriminator (IVC/volume tolerance, LV function, RV strain, pericardial effusion) is exactly what modern shock care should look like: faster pattern recognition, fewer unforced errors, and tighter reassessment after every step.

If anything, the post is also a reminder that the goal isn’t a single “correct” pathway, but it’s iterative calibration: treat, re-check perfusion, and pivot quickly as the physiology declares itself.